Part-Time Places

Technically, I live in Los Angeles.

I rent an apartment here, and my work tends to be here.

But, I haven't lived here full-time in the past 12 months, especially the last five. I was visiting some friends in Berkeley last week, and out of curiosity I did some calculations on how much time I’ve spent in each place over the past year:

Boulder, Colorado: 8 weeks

Somerville, Massachusetts: 6 weeks

Berkeley, California: 3 weeks

New York, New York: 2 weeks

Montclair, New Jersey: 1 week

Random town in Utah: 3 days (Not sure how much this counts?)

That means I spent about 32 weeks in Los Angeles, or slightly over three-fifths of my year here. Most of this travel was concentrated in the last few months when I went to live in Colorado, had an extended on/off stay in Boston, and then went to San Francisco for a week.

Honestly, 60% was better than I was expecting. Since September, I haven’t managed to be here longer than ten consecutive days. Right now, I’m at seven and holding steady!

Why was I traveling so much? I think I missed my friends. I grew up in a tight-knit community in Somerville, right outside of Boston. My first year in LA, my first away from home, had its lonely moments. I worked a remote job and lived in the sprawl of Mid-City, which is not a great combination for a person with a high social battery used to one of the densest places in the country.

Luckily, my friend Jonah missed me, too. Once a week, I would reliably get a new, vaguely desperate text message. “Boulder is the Somerville of Colorado!” “Boulder Boy Fall?” “I’m trapped in a fortune cookie factory in Boulder, Colorado!” How could I resist?

Jonah’s life in Boulder was different than my life in Los Angeles. He’s part of a subculture: Jonah is a climber.

As far as I can see, climbing is something that’s slowly creeping into mainstream culture, especially mainstream tech culture. A gym pops up in Harvard Square, and it’s mostly not people who go to competitions who start going, but grad students and bio-tech workers.

There’s a larger culture around climbing, but Jonah is part of a smaller group inside of that: people who grew up climbing, competing, know the same people, do the same boulder problems, and have the same vocabulary (tell me what “chipped” means in this context?).

Their lives are oriented around this activity differently than it might be for someone who climbs as a hobby. When my friend Ross, who grew up in Cambridge, visited us for a few days in November, he and Jonah knew the same people, talked about the same rocks, and knew the same places. These two people grew up three thousand miles from each other and had never met, yet they shared a social circle (“That’s Noah. He has the strongest fingers in the United States.”) and a common knowledge base.

There is a slippery categorical difference between these two things: Jonah and Ross are “climbers,” and your average Harvard Square Central Rock member is probably “someone who climbs.” Jonah tells me the lingo for the first group is “Core Climbers.”

That’s today’s nut I’m trying to crack: what is a subculture? How is the experience of being in a subculture different from someone who isn’t? How does this compare to other kinds of social structures? This is mostly based on my observations, so think of this as a kind of hybrid blog, journal, and amateur anthropology.

What makes it a subculture?

When I think of other examples of people who are definitely in subcultures in my life, I think of my friend Max in Berkeley.

Max is part of the effective altruism/rationalism scene in the San Francisco area.

I don’t want to bite off more than I can chew here, but effective altruism is a movement of people dedicated to critiquing and researching how we think about “doing good” and implementing those ideas in practice.

There are some controversies around this philosophy, and it can lead to some unorthodox ways of thinking about global priorities that often seem alien and/or absurd to people on the left and right.

For instance, many EAs see factory farming as one of the top issues in the world. Many on the left and right agree that this is an issue, but many EAs see this as of paramount concern. They believe that animals should be given equal weight to humans when considering suffering. At the very least, they consider this problem undervalued in terms of how much energy is put into it.

I think this is what many find both compelling and alienating about EA, depending on who you are: that there is some way to quantify issues as “more” or “less” important, which to some feels comforting and logical, and to others feels alienating and possibly judgemental of causes they’re invested in.

I have thoughts on this, but it seems outside the scope of this post. For my purposes, I want to figure out what these two groups have in common, and why they both “feel” like subcultures.

Common Values

Both of these groups have animating philosophies. It may be more obvious for Effective Altruists, who dedicate themselves to minimizing suffering in the world with literal mathematical precision.

But climbers also have a shared set of values. If you talk to these guys, they often care about environmentalism in a way that is way more concrete than the rest of us. As an example, I met one person who would otherwise probably have voted for Trump if not for his concerns about climate change. For a lot of climbers, this value set animates their other beliefs in a similar way that Effective Altruism underpins many EAs’ beliefs.

There are often shared texts like “Doing Good Better” or “The Precipice” for EA that help inform these beliefs, even if there are debates around details of the ideology within the subculture.

I don’t think a subculture must be countercultural, but inherently prioritizing certain values above other values often leads these groups to live their lives in unconventional ways. A lot of climbers prioritize climbing above other things in their lives, like a job or relationship, which are often necessary insofar as they support climbing. This leads me to…

Common Missions/Activities That Orient Life

The subcultures I’m familiar with often revolve around shared missions or specific activities, much like a job does for those in “the mainstream.”

For climbers, this is, well, climbing. For many, this is accompanied by jobs that share a commitment to the outdoors—renewable energy, working at a gym, trail maintenance—it ranges the gamut.

For EAs, this is often literally their work. The philosophy encourages people to use their working hours to solve the world’s pressing problems, from preventing pandemics to AI alignment.

The job part seems optional to being a subculture. Some climbers just climb, and some EAs just write blog posts on LessWrong. But, it does seem important that there are at least people who facilitate the culture, which is commonly done through jobs, just because of how much time and commitment it takes.

Nevertheless, subcultures tend to reorient members’ lives around an activity or work in a way that becomes part of their routines.

“Big” Community (Uppercase “C”?)

Subcultures have “big” communities. I feel like this is the most important part of subcultures I’ve observed. It separates them from “people who kind of think in similar ways and do similar things,” which can describe a lot of friend groups as well.

This was the initial distinction that made me want to write this post. Both climbers and rationalists, in their separate locations of Boulder, Colorado, and Berkeley, California, have a pretty rich network of people who participate in the common mission.

There are micro-celebrities in these networks, but usually, they’re only one to two degrees away from anyone who lives in the place. People around you, in general, know Olympic climbers or Will MacAskill in the same way that I might know some guy from college. The people who facilitate the subculture at the highest levels are not that many degrees away from any given person within the subculture.

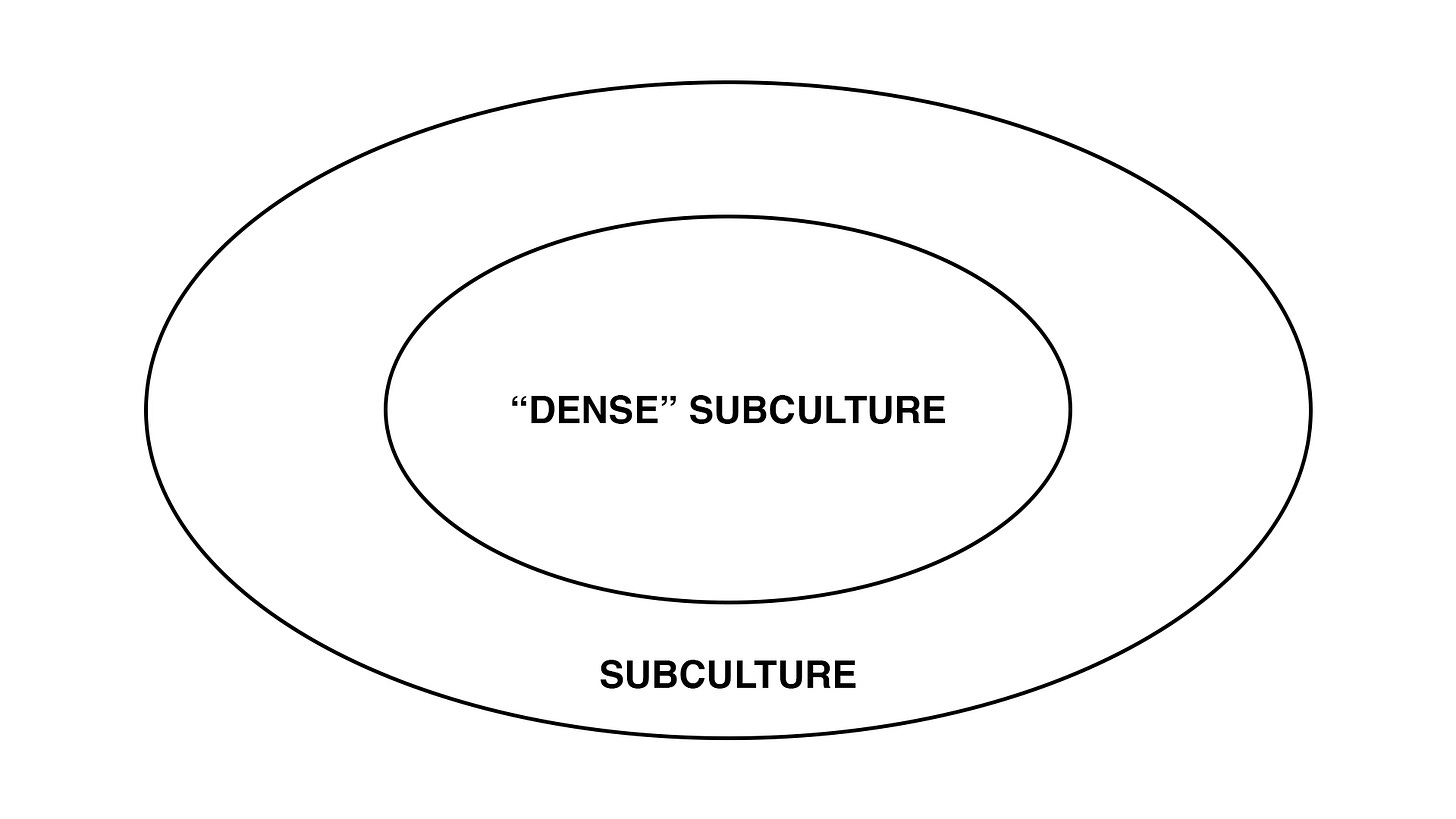

It’s possible that what I’m describing is a unique and shared phenomenon between these two areas. Perhaps there are always smaller circles within a given subculture that take you closer to micro-celebrities within that subculture, but it seems worth pointing out. These kinds of subcultures, at the very least, are dense in a way that a small/medium-sized college or academic institution is.

Maybe it’s kind of like this:

What is a “Small” Community? (lowercase “c”?)

This all feels different than how I grew up back in Boston.

I had a pretty large group of friends back in high school, and I went to college in my hometown, as people from Boston do. Because of that constant, I experienced Somerville as an ever-expanding web of social connection. We’ve pretty much all stayed in touch over the years, and there are very few people I didn’t see from high school or college when I went back home over the past month.

But what we had in common wasn’t a common activity or philosophy, and we didn’t have micro-celebrities.

What we had in common was a lot of activities, which had intersections depending on the person, some common values, and a sense of place/proximity that tied us together. My friend Desi and I would make movies together, but we were part of a larger social web that didn’t involve that activity. Max and I might have talked philosophy, but we hung out because we liked being around each other.

Even though maybe you could say that we do have a subculture through that shared web, maybe even a dense subculture because of our shared location, it doesn’t feel comparable to me.

I think a “small” community pops up out of proximity and some shared values, but they aren’t a requirement. Perhaps that’s a difference: it’s less intentional than a subculture. People go to Boulder or Berkeley to climb and be a part of the scene, but “small” communities are less structured. Maybe that’s all it is: mostly just hanging out to hang out.

Activities That Orient Life That Aren’t Subcultures

But then I think: “Haven’t I also had activities that I orient my life around? Are those subcultures?”

For instance, I produced a monthly sketch comedy show in college, which is the sort of lifestyle that is hard to explain to people who haven’t done a theater-adjacent activity.

I loved doing sketch comedy. I organized my life around it. It gave me a regular structure to write and make videos, and it was the reason I chose to go to Tufts. During my senior year of high school, I was feeling iffy about going to college or taking a gap year.

At an accepted students’ day in April, the president of the group that I would eventually join approached me and explained what they were all about. It was the first time that I was able to see myself in a place after being rejected by the top film schools I had applied to. What I loved doing in high school was making short films with my friends, and this group let me see a path for myself at a school I wasn’t sure about.

By my senior year, the group had become one of my favorite communities at college. When I began working on my senior thesis film, I chose the friends I worked with in my sketch group to help me in key roles. The work enveloped me, rotating between sketch comedy and my film seven days a week, my social circle almost entirely revolving around this group. I loved it. This era of moviemaking certainly falls into the category of an activity that oriented my life.

But I don’t think it was a subculture. We were a group of people, but we didn’t have a common set of values outside of a shared love for filmmaking. And there wasn’t a density to the network we were a part of—there were probably only 20 or 30 people at the school who were “serious” about film production. Those people certainly became my life for six months, but I feel way more comfortable throwing this into the “shared activity” bucket.

Back to Los Angeles

Admittedly, I feel like I started writing this to discover something about my life.

“Is there something missing about my life in Los Angeles?”

“Did I discover new wisdom while I was away that will fix my problems here?”

“Did I become a beatnik poet by sleeping on people’s couches for 5 months?”

But I feel like the real thing I learned was just that I like being on vacation. Also, I like hanging out with my friends, often in new places.

There was a part of me that wanted to use this as a way to identify things that are missing in Los Angeles for me in a way that they’re not for my friends in other places. Would I be happier if I was part of a subculture? Do I need some activity that orients my life, like I had in college? What about a community? Do I have that in Los Angeles?

While I think these are maybe nice concrete things to think about, I don’t know anymore. I think it’s just the attitude of touring through my friends’ lives and refreshing my curiosity that I liked. I don’t know if I want to stay in Los Angeles forever. But I also don’t have to decide that right now.

My roommates and I had a party last Sunday with a clause: everyone had to bring a friend that they thought other people at the party wouldn’t know. It was probably the best party we’ve thrown here. Not only did everyone we invited come, they all brought new people, and everyone hit it off.

Community can be hard to find in a city like Los Angeles. The architecture isn’t suited to it. You spend a third of your day in your car, and the humanity you might find on a train or bus is drowned out in a sea of private freeway fortresses. Everywhere is far apart. When you walk down the street, which is always wide with a thin sidewalk, there is no one around. Buildings feel cold and empty on the outside. One of the first things I noticed when I moved here is that it can be eerily quiet for one of the biggest cities in America. It’s a big contrast to Somerville, New York, or anywhere else I’ve lived.

And despite the city’s almost singular focus on entertainment, the work can feel isolating and overly competitive. The film industry isn’t a subculture or a group activity; it’s a cutthroat competition. Or, maybe it can feel that way with the wrong attitude.

My friends and I have started to carve out a community out here. And it’s not the same as a community in Somerville, Berkeley, or Boulder. It’s new, it takes different shapes, and it has its strengths and drawbacks. People value fun more on the West Coast. There isn’t the same need to intellectualize everything that there is back East.

If I have a New Year’s resolution, it’s to take the attitude that I have about other places here: treat it as one big vacation. I probably won’t be here forever, but I can appreciate it for what it is, instead of judging it for what it isn’t.

Song of the Week: First Time by Lucy Dacus

Where did we go right? I think about it all the time.

If I had paid closer attention, maybe I could take us back there and then.

You can feel it for the first time, the second time.